what to do about people in communities targeting a person and trying to make them into a criminal

This module is a resource for lecturers

Topic 2 continued - Detailed caption of Tonry and Farrington's typology

This department provides a detailed explanation of the crime prevention approaches included in Tonry and Farrington's typology. By covering each in more detail, important theories and concepts will exist introduced and some of the challenges of implementing each type of crime prevention will be explored.

Developmental criminal offence prevention

Developmental law-breaking prevention focuses on early on intervention through the reduction of risk factors associated with afterwards criminality and the strengthening of protective factors (France and Homel, 2007; Farrington and Welsh, 2007). There is growing evidence of the success of developmental crime prevention and early on intervention:

[F]indings of neuroscience, behavioural research, and economics show a "hitting convergence on a set of common principles that account for the potent effects of early on environs on the chapters of human skill evolution", which affirms the need for greater investments in disadvantaged children in the early on years of the life form (Knudsen et al., 2006 every bit cited in Welsh et al., 2010, p. 115).

An Australian expert on developmental criminology, Professor Ross Homel (and his co-writer Lisa Thomsen), annotation:

Developmental prevention involves the utilize of scientific enquiry to guide the provision of resources for individuals, families, schools or communities to address the conditions that give rise to anti-social behaviour and crime earlier these issues arise, or before they go entrenched … Doing something virtually law-breaking early, preferably earlier the damage is too hard to repair, strikes well-nigh people as a logical arroyo to criminal offence prevention. The twin challenges, of course, are to place exactly what it is in individuals, families, schools and communities that increases the odds of involvement in crime and so to do something useful about the identified conditions as early every bit possible (Homel and Thomsen, 2017, p. 57).

Withal, assessing who is at risk of future offending, isolating the reasons for this increased run a risk and then finer intervening to forbid future onset of criminality are difficult tasks. Farrington and Welsh (2007) help guide our understanding of some of the critical take a chance factors associated with later offending and the types of intervention which appear to exist most effective, through the post-obit:

| Risk Factors | Evidence-Based Interventions |

| Individual:

| Private:

|

| Family:

| Family unit:

|

| Environmental:

| Environmental:

|

While this data provided by Farrington and Welsh (2007) is specially helpful in understanding disquisitional adventure factors and forms of intervention, it does not necessarily help with the hard tasks associated with designing and implementing a developmental law-breaking prevention programme. These tasks can exist especially challenging. Ensuring the right groups and individuals participate in the programme; ensuring that the mechanisms for change are well understood and addressed through the intervention; having accordingly trained program staff and closely monitoring the bear upon of the intervention are simply some of the challenges of implementing developmental offense prevention programmes.

In addition to these challenges, programmes and interventions can operate at different levels, including the following:

- Universal - general population

- Selected - directed at groups judged to be at increased risk

- Indicated - directed at individuals already manifesting a problem such equally disruptive behaviour (Homel, 2005)

This means that crime prevention initiatives crave that decisions be made about the target population of a programme or intervention, with implications in terms of cost, recruitment of participants, potential problems with stigmatizing communities, families or individuals. These factors bear meaning influence on the strategies required to ensure effectively delivery of appropriate programmes for the specific populations.

Moreover, it is of import to acknowledge that the isolation or identification of risk factors, such as those listed above, are the subject of criticism. Concerns accept been raised about the stigmatising potential of identifying that growing upwards in a low socio-economic condition household, for example, is a risk factor for crime. For some, this equates to stigmatising the poor and diverts attention from the structural factors contributing to poverty while focusing on the individual victims of these structural disadvantages.

The following table provides helpful guidance on aspects of programme development and implementation.

| Think Developmentally | Practice Good Science |

|

|

| Understand Community Needs | Engage in Customs Development |

|

|

(Source: Batchelor et al., 2006, p. 2)

Community law-breaking prevention

Hope (1995, p. 21) suggests that "community criminal offense prevention refers to actions intended to modify the social atmospheric condition that are believed to sustain crime in residential communities. Information technology concentrates unremarkably on the power of local social institutions to reduce criminal offense in residential neighbourhoods".

In this context, "the structure and organisation of a community affects the crime it experiences over and above the individual characteristics of its residents" (Hope and Shaw 1988 as cited in Hogg and Brownish, 1998, p. 190). This means that the community (however customs might be defined) is greater than but the sum of its residents - there are effects arising from the way residents interact, the opportunities that they take bachelor to them, the services provided for them, and the relationships between them - both collectively and with relevant service providers and agencies.

Hence, this arroyo focuses on residential communities and neighbourhoods, and seeks to change the social atmospheric condition associated with crime. Nevertheless, identifying what social conditions should be inverse and finding ways to practice this are not straightforward tasks.

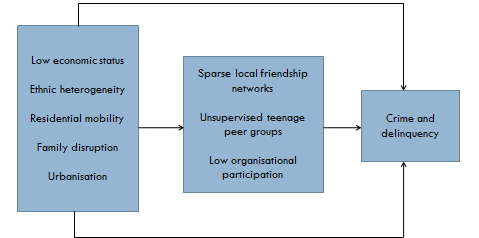

This arroyo to criminal offense prevention has its roots, in part, in the Chicago School and the focus on social disorganization. Sampson and Groves annotation:

In full general terms, social disorganisation refers to the disability of a community structure to realise the common values of its residents and maintain constructive social controls. Empirically, the structural dimensions of customs social disorganisation can be measured in terms of the prevalence and interdependence of social networks in a customs - both informal (eastward.g. friendship ties) and formal (due east.g. organisational participation) - and in the bridge of commonage supervision that the customs directs toward local bug ... structural barriers impede development of the formal and informal ties that promote the ability to solve mutual problems (see diagram on the post-obit folio). Social organisation and disorganisation are thus seen as different ends of the aforementioned continuum with respect to systematic networks of customs social command. (1989. p. 777)

The structural barriers that can impede the development of formal and informal ties identified by the Chicago School (in particular Shaw and McKay, cited in Sampson and Groves, 1989), are demonstrated in the following diagram. This diagram shows how broad, structural issues similar socio-economical status, residential mobility, and how people and families settle in communities and build connections with neighbours and peers, can contribute to incidents of crime in cases where there are low levels of informal social control and collective efficacy.

Source: Causal model of extended version of Shaw and McKay'southward theory of community systemic construction and rates of criminal offence and delinquency, cited in (Sampson and Groves, 1989, p. 783).

Generally speaking, elevated levels of informal social control and collective efficacy in local communities effect in lower crime. The following provides an insight into the nature of these constructs:

Sampson and his co-authors then introduced the term 'collective efficacy', which is defined in terms of the neighbourhood'southward power to maintain order in public spaces such every bit streets, sidewalks, and parks. Collective efficacy is implemented when neighbourhood residents take over actions to maintain public lodge, such every bit past complaining to the regime or by organizing neighbourhood lookout man programs. The authors argued that residents take such actions only when 'cohesion and mutual trust' in the neighbourhood is linked to 'shared expectations for intervening in support of neighbourhood social control'. If either the common trust or the shared expectations are absent, so residents will be unlikely to act when disorder invades public space (Vold et al., 2002, p. 131-132).

Thus, the focus of community criminal offence prevention is on strengthening communities through the provision of services that build connections betwixt community members and connect them to external resources and services that tin can help them combat crime (including the police force, health agencies, civil society and non-regime organizations). This multi-sectoral context requires agencies to piece of work together, which is not always straight forward. Constructive inter-agency crime prevention requires: the sharing of data to help empathise the nature of the crime problem(south); the development of coordinated plans for service delivery; the maintenance of regular communication; and joint assessment of the impact of intervention(south).

Situational law-breaking prevention

One of the about significant proponents of situational criminal offense prevention, Professor Ron Clarke, offers the post-obit clarification of situational offense prevention:

Situational law-breaking prevention comprises opportunity-reducing measures that are (1) directed at highly specific forms of criminal offense, (2) that involve the direction, pattern or manipulation of the immediate surroundings in as specific and permanent style as possible, (iii) then as to increase the try and risk of law-breaking and reduce the rewards as perceived past a wide range of offenders. (1997. p. 4)

This model of crime prevention assumes that many offenders are rational and respond to available opportunities for offending. If offending is difficult, then there will be a reduced propensity to offend; where offending is left unchecked, then offending will escalate. It is assumed that an offender weighs up the benefits derived from offending, the potential risks of existence apprehended and the associated costs of anticipation. The results of this calculation volition decide if an offence is committed.

This model also builds on the routine activities theory. Felson and Cohen advise that:

... any successfully completed violation requires at a minimum an offender with both criminal inclinations and the ability to deport out those inclinations, a person or object providing a suitable target for the offender, and the absence of capable guardians capable of preventing the violation. (1980, p. 392)

This can be demonstrated by the crime triangle below:

Addressing these 3 elements of crime can help to prevent criminal offence.

During the same catamenia (the late 1970s/early 1980s) that Felson and Cohen were developing the Routine Activities Theory, the Brantinghams were analysing spatial and temporal crime trends (see Brantingham and Brantingham, 1978; 1981; 1982). From their research, they concluded that:

Crimes exercise not occur randomly or uniformly in time or space or society. Crimes exercise non occur randomly or uniformly beyond neighbourhoods, or social groups, or during an individual's daily activities or during an individual'due south lifetime ... There are hot spots and cold spots; there are high repeat offenders and high repeat victims. In fact the two groups are frequently linked. While the numbers will continue to be debated depending on the definition and population existence tested, a very small proportion of people commit most of the known crimes and likewise account for a large proportion of victimisations. (2008, p. 79)

Echoing Felson and Cohen (1980), the Brantinghams drew attention to routine activities. They suggested that individuals undertake a range of regular activities in unlike nodes (home, work, schoolhouse, shopping, amusement). These activeness nodes are connected past paths and people tend to routinely travel forth the same paths in going nigh their daily routines. Consequently, individuals incidentally observe and learn virtually potential opportunities for crime. When a potential offender intersects with a potential target or victim, the latter will go an actual target when the potential offender'south willingness to commit a criminal offense has been triggered. These patterns of daily activities and routines help to explain why particular locations experience elevated rates of crime - a phenomenon known as 'criminal offense blueprint theory'.

The Brantinghams suggest that it is possible to predict offense hot spots based on an understanding of these dynamics. By analysing specific locations and considering the convergence of the fundamental elements of law-breaking design theory, it is possible to predict where criminal offence will be concentrated.

Together the rational option offender approach, the routine activities theory and the crime blueprint theory reveal how opportunities for law-breaking arise in particular locations at detail times. They promote an agreement of the dynamics of offending, including important spatial and temporal trends. They operate on the basis that offending is a rational, purposive act that occurs when a sufficiently motivated person encounters a suitable target or victim in the absence of capable guardianship. These approaches also encourage deeper analysis of the specific decisions associated with offending and how they are impacted by the availability of opportunities for crime.

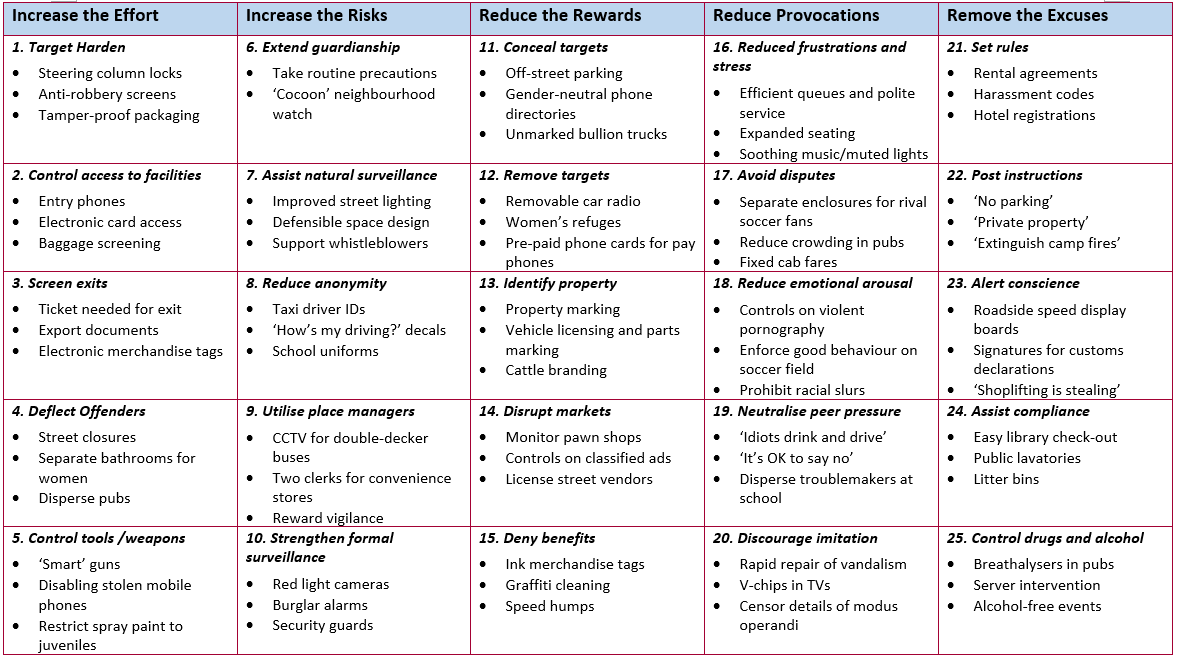

In response to these explanations for criminal offence, the following can be instituted to prevent offending:

- Increase the effort

- Increment the risks

- Reduce the rewards

- Reduce provocations

- Remove the excuses

Cornish and Clarke (2003) have expanded these to 25 opportunity reducing techniques [ Open table as pdf].

(Source: Cornish and Clarke, 2003).

While there is very strong evidence that various forms of situational crime prevention are very constructive at reducing law-breaking, critics often fence that crime prevention efforts just displace crime (move information technology from ane area or location to another). Despite these claims, it has been mostly established that displacement of crime does non back-trail all law-breaking prevention interventions and even where there is prove of displacement, not all crime moves. For example, i study by Hesseling (1994) found "no evidence of deportation in 22 of the studies he examined; in the remaining 33 studies, he found some show of displacement, only in no case was there as much crime displaced equally prevented" (this study is cited in Clarke, 2008, p. 188). In contrast, there is increasing evidence that rather than displacing crime, preventive measures might actually issue in a 'diffusion of benefits', which is the reduction in crime beyond the immediate focus of measures introduced. In this context, the net crime benefits are greater than might have been anticipated by a particular intervention considering not only is criminal offence prevented in the target area, only is besides prevented in adjacent areas.

Crime prevention through environmental design

Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED) according to Crowe, is based on the notion that the:

physical environs can be manipulated to produce behavioural effects that volition reduce the incidence and fear of crime, thereby improving the quality of life. These behavioural furnishings tin can be accomplished by reducing the propensity of the physical environment to support criminal behaviour (Crowe, 2000, p. 34-five).

Blocking opportunities for criminal offence through creating obstacles or barriers to targets; eliminating places for concealment of would-exist offenders; restricting escape routes; and increasing the surveillance of would-exist offenders (Rosenbaum, Lurigio and Davis, 1998, p. 125-vi) are all ways that the concrete environment can be manipulated to foreclose criminal offence.

More specifically, CPTED at present unremarkably includes a serial of design techniques, which Cozens et al (2005) list every bit:

- Surveillance: natural and technical surveillance increases the risks for would-exist offenders. Surveillance can be achieved through promoting 'eyes on the street', as advocated by Jane Jacobs, through land employ to maximise the presence of pedestrians throughout the twenty-four hours and nighttime, or technical surveillance using closed excursion television (CCTV). A concrete example of design that facilitates natural surveillance, is ensuring that trees and shrubs do non interfere with street lighting. Further examples of pattern that achieves natural surveillance are bachelor on the interactive website Secured by Design;

- Access control: blocking admission to venues and items reduces the opportunities for crime. This might be in the form of fencing, landscaping, and video and telephone activated entry to residential areas;

- Territoriality: designing in a sense of ownership over a space promotes territoriality. Owners of a space will oftentimes arbitrate if in that location is anti-social behaviour. Blueprint can influence the likelihood of such action being taken or not;

- Activity support: public spaces can be activated using music or performances which draw people into a space. The presence of people will often make an area feel safer;

- Image/maintenance: maintaining an expanse helps to send cues about capable guardianship. An expanse that appears not to exist maintained or cared for might invite illicit activity. The removal of rubbish removal from parks, and the maintenance of public infrastructure such equally charabanc shelters and public toilets are examples of the investment in maintenance that can assist with crime prevention. Conversely an expanse that suggests high levels of capable guardianship will be less likely to attract illicit activity; and

- Target hardening: hardening targets makes them less attractive to would-exist offenders. This might include installing security devices to make items less likely to be stolen. Another example is the installation of concrete bollards to prevent vehicle attacks on physical property or entry to pedestrian zones.

CPTED and situational prevention belong to a 'family' of similar preventive approaches. Situational prevention seeks to eliminate existing issues, whereas CPTED seeks to "eliminate anticipated bug in new designs on the basis of past experience with similar designs" (Clarke, 2008, p. 182). Thus, Clarke suggests that CPTED is more future looking than situational prevention.

CPTED has really gained widespread interest in recent decades and is now practiced in numerous ways. Many constabulary and local potency staff now receive CPTED training; in some jurisdictions rating systems for some forms of built environment quantify safety and security (for case, the Secured by Pattern accreditation process in the United Kingdom (U.k.)); CPTED practitioner professional associations accept emerged (for example, the International CPTED Association); and many planning regimes at present routinely incorporate CPTED design principles.

Useful resources on CPTED include:

- The United Nations Interregional Law-breaking and Justice Research Institute has published a detailed report on CPTED

- The UK Secured by Design interactive design guideline is a tool that can be used to demonstrate key features of CPTED

Police force enforcement / criminal justice law-breaking prevention

Criminal justice offense prevention refers to the activities of the criminal justice system that seek to reduce the incidence and severity of offense. Consequently, criminal justice criminal offence prevention includes a diverse range of initiatives, such as various police activities through to post-release support programmes for people leaving prison house. Comprehensive coverage of all possible criminal justice offense prevention interventions is beyond the scope of this Module. Relevant information is contained in the following Modules:

- Module 5: Police force Accountability, Integrity and Oversight

- Module half-dozen: Prison Reform

- Module 7: Alternatives to Imprisonment

- Module 8: Restorative Justice

The following definition of criminal justice crime prevention gives some sense of the diversity of activities captured by this approach:

[Criminal justice criminal offence prevention] deals with offending afterwards it has happened, and involves intervention in the lives of known offenders in such a fashion that they will non commit further offences. In then far as it is preventative, information technology operates through incapacitation and private deterrence, and possibly offers the opportunity of treatment in prisons or through other sentencing options. (Cameron and Laycock, 2002, p. 314)

This definition highlights the importance of courts and corrections (including prisons and customs corrections) in forestalling or preventing hereafter offending. It speaks to fundamental criminological and criminal law concepts, such as incapacitation, deterrence, rehabilitation, and restoration.

Policing

Police seek to prevent offense in various ways. Different models of policing focus on dissimilar tactics and approaches to prevent or reduce crime. 3 mutual forms of policing that potentially upshot in quite different approaches to crime prevention include:

- Community-based policing: this arroyo recognizes that police are of the people and for the people. Without customs support police are not very effective because a considerable amount of crime is cleared due to reports from customs members. Community-based policing favours tactics which connect the constabulary to local communities. This might exist through police force involvement in community events; the cosmos of law-community committees to found local policing priorities; and the creation of community-based roles to assist the law connect with difficult-to-achieve groups such as those from minority communities.

- Problem-oriented policing: this approach, developed by Professor Herman Goldstein, seeks to ensure a more responsive policing. Rather than only responding to calls for service, Goldstein suggested that issues should be defined with much greater specificity; that effort needs to exist invested in researching the problem; that alternative solutions should be considered (including physical and technical changes, changes in the provision of regime services, developing new customs resources, increased use of city ordinances, and improved utilise of zoning); and that implementation should be carefully managed (Goldstein, 1979, p. 244-58). This arroyo utilizes the SARA model which will be explained in detail under "Topic Three".

- Pulling levers of focused deterrence policing: this approach, developed by Professor David Kennedy and his colleagues, seeks to preclude crime through: detailed analysis of pressing crime problems; communicating with high chance offenders; providing swift policing resources if these loftier risk offenders go on to offend, while also extending opportunities to exit crime through engaging with relevant support services; and mobilizing local community voices to condemn ongoing criminal (peculiarly tearing) activity. This approach relies and coordination of various services, including police, probation and parole, prosecutors, welfare services, youth workers, local community members impacted by crime, and other agencies. Effectiveness rests on both the swift delivery of a policing and criminal justice response if offending persists, and the provision of opportunities to cease offending.

More detailed commentary about approaches and specific case studies of policing urban space can be found in the Introductory Handbook on Policing of Urban Space developed by UNODC and UN-HABITAT (2011).

Courts

Courts seek to contribute to the prevention of crime in various ways. General and specific deterrence are goals of sentencing and court processes. By actualization in court and existence sentenced, it is expected that offenders will be deterred from committing further offense. This might be due to the shame associated of actualization in courtroom; the recognition of wrongdoing through the court process; or the services that might be accessed to help rehabilitation. In many jurisdictions courts take, in recent years, sought to develop more than creative means to reduce reoffending. Drug and other specialist courts seek to provide appropriate assessment and treatment for offenders with demonstrable drug or other issues. In this style, courts go more closely linked to handling that will assist to reduce the risk factors associated with ongoing offending.

Prison and postal service-release support

In theory, at least, prison provides opportunities for rehabilitation. This might come up in multiple forms, including through instruction and employment programmes, therapeutic interventions, work release, and individual counselling and/or casework. These interventions might seek to accost risk factors associated with offending, fix a prisoner for return to the community, or provide them with the qualifications and skills to seek gainful employment.

Post-release support has been recognized as being critical to helping ex-prisoners return to the community and to overcome mail service-release risks (which include homelessness, overdose, suicide and re-offending). Post-release back up can take various forms and include the provision of accommodation, ongoing counselling or instance management, assistance gaining piece of work, and more controlling measures such every bit electronic monitoring and urinalysis.

Together, these interventions take the potential to reduce the risks of recidivism, an of import facet of crime prevention.

Next: Topic three - Crime problem-solving approaches

Next: Topic three - Crime problem-solving approaches

Back to height

Back to height

Source: https://www.unodc.org/e4j/zh/crime-prevention-criminal-justice/module-2/key-issues/2a--detailed-explanation-of-tonry-and-farringtons-typology.html

0 Response to "what to do about people in communities targeting a person and trying to make them into a criminal"

Post a Comment