what happendd to constable daniel in dr blake mysteries after season one

The Whitechapel murders were committed in or nearly the largely impoverished Whitechapel district in the East End of London between 3 April 1888 and xiii February 1891. At various points some or all of these xi unsolved murders of women have been ascribed to the notorious unidentified series killer known as Jack the Ripper.

Most, if not all, of the victims—Emma Elizabeth Smith, Martha Tabram, Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Step, Catherine Eddowes, Mary Jane Kelly, Rose Mylett, Alice McKenzie, Frances Coles, and an unidentified woman—were prostitutes. Smith was sexually assaulted and robbed by a gang. Tabram was stabbed 39 times. Nichols, Chapman, Stride, Eddowes, Kelly, McKenzie and Coles had their throats cut. Eddowes and Pace were murdered on the same night, within approximately an hour and less than a mile apart; their murders are known as the "double issue", after a phrase in a postcard sent to the press by an private challenge to be the Ripper. The bodies of Nichols, Chapman, Eddowes and Kelly had abdominal mutilations. Mylett was strangled. The body of the unidentified woman was dismembered, simply the exact crusade of her death is unclear.

The Metropolitan Police, City of London Police, and private organisations such as the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee were actively involved in the search for the perpetrator or perpetrators. Despite extensive enquiries and several arrests, the culprit or culprits evaded capture, and the murders were never solved. The Whitechapel murders drew attention to the poor living conditions in the East End slums, which were subsequently improved. The enduring mystery of who committed the crimes has captured public imagination to the present solar day.

Background [edit]

In the late Victorian era, Whitechapel was considered to exist the most notorious criminal rookery in London. The area around Blossom and Dean Street was described as "maybe the foulest and well-nigh unsafe street in the whole metropolis";[1] Dorset Street was called "the worst street in London".[ii] Assistant Law Commissioner Robert Anderson recommended Whitechapel to "those who accept an involvement in the dangerous classes" every bit one of London's prime criminal "show places".[three] Robbery, violence and alcohol dependency were commonplace. The district was characterised past extreme poverty, sub-standard housing, poor sanitation, homelessness, drunkenness and endemic prostitution. These factors were focused in the institution of the 233 common lodging-houses inside Whitechapel, in which approximately 8,500 people resided on a nightly ground.[iv]

The common lodging-houses in and around Whitechapel provided cheap communal lodgings for the desperate, the destitute and the transient, among whom the Whitechapel murder victims were numbered.[v] The nightly price of a unmarried bed was 4d,[half-dozen] and the cost of sleeping upon a "lean-to" rope stretched across the bedrooms was 2d for adults or children.[7]

All the identified victims of the Whitechapel murders lived within the heart of the rookery in Spitalfields, including iii in George Street (later named Lolesworth Street), ii in Dorset Street, two in Flower and Dean Street and one in Thrawl Street.[8]

Constabulary work and criminal prosecutions at the time relied heavily on confessions, witness testimony, and apprehending perpetrators in the act of committing an offence or in the possession of obvious physical evidence that clearly linked them to a criminal offense. Forensic techniques, such as fingerprint analysis, were not in use,[nine] and blood typing had not been invented.[10] Policing in London was—and nonetheless is—divided between two forces: the Metropolitan Constabulary with jurisdiction over well-nigh of the urban area, and the City of London Police with jurisdiction over about a square mile (2.9 km2) of the urban center centre. The Home Secretary, a senior government minister of the British government, controlled the Metropolitan Police, whereas the City Police were responsible to the Corporation of London. Beat constables walked regular, timed routes.[11]

Eleven deaths in or most Whitechapel between 1888 and 1891 were gathered into a unmarried file, referred to in the police force docket as the Whitechapel murders.[12] [13] Much of the original textile has been either stolen, lost, or destroyed.[12]

Victims and investigation [edit]

Map of the Spitalfields rookery, where the victims lived. Emma Elizabeth Smith was attacked near the junction of Osborn Street and Brick Lane (red circle). She lived in a common lodging-house at xviii George Street (later named Lolesworth Street), one block west of where she was attacked.[14]

Emma Elizabeth Smith [edit]

On Tuesday 3 April 1888, following the Easter Monday banking concern holiday, 45-year-old prostitute Emma Elizabeth Smith was assaulted and robbed at the junction of Osborn Street and Brick Lane, Whitechapel, in the early hours of the morning. Although injured, she survived the assail and managed to walk back to her lodging firm at 18 George Street, Spitalfields. She told the deputy keeper, Mary Russell, that she had been attacked by two or three men, 1 of them a teenager. Russell took Smith to the London Infirmary, where a medical exam revealed that a blunt object had been inserted into her vagina, rupturing her peritoneum. She developed peritonitis and died at 9 am the post-obit twenty-four hour period.[fifteen]

The inquest was conducted on 7 April past the coroner for E Middlesex, Wynne Edwin Baxter, who too conducted inquests on half dozen of the later victims.[16] The local inspector of the Metropolitan Law, Edmund Reid of H Partition Whitechapel, investigated the attack simply the culprits were never defenseless.[17] Walter Dew, a detective constable stationed with H Division, later wrote that he believed Smith to be the first victim of Jack the Ripper,[18] but his colleagues suspected her murder was the piece of work of a criminal gang.[nineteen] Smith claimed that she was attacked by 2 or 3 men, merely either refused to or could not describe them beyond stating i was a teenager.[20] Eastward End prostitutes were often managed by gangs, and Smith could have been attacked by her pimps as a punishment for disobeying them, or every bit an deed of intimidation.[21] She may not accept identified her attackers because she feared reprisal. Her murder is considered unlikely to be connected with the afterwards killings.[12] [22]

Martha Tabram [edit]

On Tuesday 7 August, post-obit a Monday bank holiday, prostitute Martha Tabram was murdered at about 2:30 am. Her body was found at George Yard Buildings, George G, Whitechapel, before long before 5:00 a.m. She had been stabbed 39 times about her cervix, torso and genitals with a short bract. With one possible exception, all her wounds had been inflicted by a correct-handed individual.[24]

On the basis of statements from a fellow prostitute, and PC Thomas Barrett who was patrolling nearby, Inspector Reid put soldiers at the Belfry of London and Wellington Barracks on an identification parade, merely without positive results.[25] Police force did non connect Tabram'southward murder with the before murder of Emma Smith, but they did connect her death with afterwards murders.[26]

Most experts do not connect Tabram's murder with the others attributed to the Ripper, because she had been repeatedly stabbed, whereas later victims typically suffered slash wounds and intestinal mutilations. Withal, a connection cannot be ruled out.[27]

Mary Ann Nichols [edit]

On Friday 31 August, Mary Ann Nichols was murdered in Buck's Row (since renamed Durward Street), a dorsum street in Whitechapel. Her torso was discovered past cart driver Charles Cross at 3:45 am on the ground in front of a gated stable archway. Her throat had been slit twice from left to correct and her abdomen was mutilated by a deep jagged wound. Several shallower incisions across the abdomen, and iii or four similar cuts on the right side were caused past the same knife used violently and downwards.[29] As the murder occurred in the territory of the J or Bethnal Green Division of the Metropolitan Police, it was at offset investigated by the local detectives. On the same twenty-four hours, James Monro resigned as the head of the Criminal Investigation Section (CID) over differences with Master Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police force Sir Charles Warren.[thirty]

Initial investigations into the murder had little success, although elements of the press linked information technology to the two previous murders and suggested the killing might have been perpetrated by a gang, equally in the instance of Smith.[31] The Star paper suggested instead that a single killer was responsible and other newspapers took up their storyline.[32] [33] Suspicions of a serial killer at big in London led to the secondment of Detective Inspectors Frederick Abberline, Henry Moore and Walter Andrews from the Central Office at Scotland Yard.[34] On the bachelor testify, Coroner Baxter ended that Nichols was murdered at but afterwards 3 am where she was establish. In his summing up, he dismissed the possibility that her murder was connected with those of Smith and Tabram, as the lethal weapons were different in those cases, and neither of the earlier cases involved a slash to the throat.[35] However, by the fourth dimension the inquest into Nichols's death had concluded, a 4th adult female had been murdered, and Baxter noted "The similarity of the injuries in the two cases is considerable."[36]

Annie Chapman [edit]

The mutilated body of the fourth woman, Annie Chapman, was discovered at about half-dozen:00 am on Saturday viii September on the footing almost a doorway in the back grand of 29 Hanbury Street, Spitalfields. Chapman had left her lodgings at ii am on the day she was murdered, with the intention of getting money from a client to pay her rent.[38] Her throat was cut from left to right. She had been disembowelled, and her intestines had been thrown out of her abdomen over each of her shoulders. The morgue test revealed that office of her uterus was missing. The pathologist, George Bagster Phillips, was of the opinion that the murderer must have possessed anatomical noesis to have sliced out the reproductive organs in a single movement with a blade almost 6–8 inches (15–20 cm) long.[39] However, the thought that the murderer possessed surgical skill was dismissed by other experts.[40] As the bodies were not examined extensively at the scene, it has too been suggested that the organs were actually removed by mortuary staff, who took advantage of bodies that had already been opened to excerpt organs that they could sell equally surgical specimens.[41]

On 10 September, the police arrested a notorious local chosen John Pizer, dubbed "Leather Apron", who had a reputation for terrorising local prostitutes. His alibis for the two most recent murders were corroborated, and he was released without accuse.[42] At the inquest i of the witnesses, Mrs Elizabeth Long, testified that she had seen Chapman talking to a man at about v:30 am just beyond the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street, where Chapman was afterwards institute. Baxter inferred that the man Mrs Long had seen was the murderer. Mrs Long described him equally over forty, a little taller than Chapman, of dark complexion, and of foreign, "shabby-genteel" appearance.[43] He was wearing a chocolate-brown deer-stalker hat and a dark overcoat.[43] Another witness, carpenter Albert Cadosch, had entered the neighbouring yard at 27 Hanbury Street at well-nigh the same time, and heard voices in the yard followed by the sound of something or someone falling confronting the fence.[44]

In his memoirs, Walter Dew recorded that the killings caused widespread panic in London.[45] A mob attacked the Commercial Road law station, suspecting that the murderer was being held in that location.[46] Samuel Montagu, the Member of Parliament for Whitechapel, offered a reward of £100 (roughly £11,000 as of 2022) afterward rumours that the attacks were Jewish ritual killings led to anti-Semitic demonstrations.[47] Local residents founded the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee nether the chairmanship of George Lusk and offered a reward for the anticipation of the killer—something the Metropolitan Police (nether instruction from the Abode Function) refused to do because such a move could lead to false or misleading data.[48] The Committee employed two private detectives to investigate the case.[49]

Robert Anderson was appointed head of the CID on 1 September, but he went on sick leave to Switzerland on the 7th. Superintendent Thomas Arnold, who was in charge of H (Whitechapel) Division, went on leave on 2 September.[50] Anderson'southward absence left overall direction of the enquiries confused, and led Chief Commissioner Sir Charles Warren to appoint Master Inspector Donald Swanson to co-ordinate the investigation from Scotland One thousand.[51] A German barber named Charles Ludwig was taken into custody on 18 September on suspicion of the murders, but he was released less than two weeks afterwards when a double murder demonstrated that the real culprit was still at big.[47] [52]

Double event: Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes [edit]

On Sunday thirty September, the body of prostitute Elizabeth Stride was discovered at almost 1 am in Dutfield's M, inside the gateway of 40 Berner Street (since renamed Henriques Street), Whitechapel. She was lying in a pool of claret with her pharynx cut from left to right. She had been killed simply minutes before, and her trunk was otherwise unmutilated. It is possible that the murderer was disturbed earlier he could commit any mutilation of the trunk by someone entering the yard, perhaps Louis Diemschutz, who discovered the body.[54] However, some commentators on the case conclude that Pace's murder was unconnected to the others[55] on the ground that the body was unmutilated, that information technology was the only murder to occur south of Whitechapel Road,[56] and that the blade used might have been shorter and of a different design.[54] Most experts, nevertheless, consider the similarities in the case distinctive enough to connect Stride's murder with at least two of the earlier ones, also as that of Catherine Eddowes on the aforementioned dark.[57]

At one:45 am Catherine Eddowes's mutilated torso was found past PC Edward Watkins at the s-west corner of Mitre Foursquare, in the City of London, about 12 minutes walk from Berner Street.[58] She had been killed less than x minutes earlier past a slash to the throat from left to right with a precipitous, pointed pocketknife at least 6 inches (fifteen cm) long.[59] Her face and abdomen were mutilated, and her intestines were drawn out over the correct shoulder with a detached length between her trunk and left arm. Her left kidney and most of her uterus were removed. The Eddowes inquest was opened on four Oct past Samuel F. Langham, coroner for the City of London.[60] The examining pathologist, Dr Frederick Gordon Chocolate-brown, believed the perpetrator "had considerable knowledge of the position of the organs" and from the position of the wounds on the body he could tell that the murderer had knelt to the right of the body, and worked alone.[61] However, the first physician at the scene, local surgeon Dr George William Sequeira, disputed that the killer possessed anatomical skill or sought particular organs.[62] His view was shared by City medical officer William Sedgwick Saunders, who was too nowadays at the autopsy.[63] Because of this murder's location, the Urban center of London Police nether Detective Inspector James McWilliam were brought into the enquiry.[64]

Catherine Eddowes, 46, lived with partner John Kelly in a lodging-house at 55 Flower and Dean Street.[65]

At three am a blood-stained fragment of Eddowes's apron was establish lying in the passage of the doorway leading to 108 to 119 Goulston Street, Whitechapel, most a third of a mile (500 1000) from the murder scene. There was chalk writing on the wall of the doorway, which read either "The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing"[66] [67] or "The Juwes are not the men who will be blamed for null."[68] At five am, Commissioner Warren attended the scene and ordered the words erased for fear that they would spark anti-Semitic riots.[69] Goulston Street was on a direct road from Mitre Foursquare to Flower and Dean Street, where both Stride and Eddowes lived.[70]

The Middlesex coroner, Wynne Baxter, believed that Pace had been attacked with a swift, sudden activity.[71] She was still holding a package of cachous (breath freshening sweets) in her left hand when she was discovered,[72] indicating that she had not had fourth dimension to defend herself.[73] A grocer, Matthew Packer, implied to private detectives employed by the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee that he had sold some grapes to Step and the murderer; nonetheless, he had told police that he had shut his store without seeing annihilation suspicious.[74] At the inquest, the pathologists stated emphatically that Stride had not held, swallowed or consumed grapes.[75] They described her stomach contents every bit "cheese, potatoes and farinaceous powder [flour or milled grain]".[76] Still, Packer'southward story appeared in the press.[77] Packer'southward clarification of the man did not friction match the statements by other witnesses who may have seen Pace with a man presently before her murder, merely all only two of the descriptions differed.[78] Joseph Lawende passed through Mitre Square with two other men shortly before Eddowes was murdered in that location, and may have seen her with a man of virtually thirty years onetime, who was shabbily dressed, wore a peaked cap, and had a fair moustache.[79] Chief Inspector Swanson noted that Lawende'southward description was a almost match to another provided by one of the witnesses who may have seen Stride with her murderer.[80] Yet, Lawende stated that he would not be able to identify the man again, and the 2 other men with Lawende were unable to give descriptions.[81]

Criticism of the Metropolitan Police and the Home Secretary, Henry Matthews, continued to mountain as little progress was fabricated with the investigation.[82] The City Police and the Lord Mayor of London offered a reward of £500 (roughly £57,000 as of 2022) for information leading to the capture of the villain.[83] The use of bloodhounds to rail the killer in the event of another attack was considered and a trial was held in London merely the idea was abandoned because the trail of scents was dislocated in the busy metropolis, the dogs were inexperienced in an urban environment, and the owner Edwin Brough of Wyndyate virtually Scarborough (at present Scalby Manor) was concerned that the dogs would exist poisoned by criminals if their function in law-breaking detection became known.[84]

On 27 September, the Cardinal News Agency received a letter, dubbed the "Love Boss" letter of the alphabet, in which the writer, who signed himself "Jack the Ripper", claimed to have committed the murders.[85] On 1 October, a postcard, dubbed the "Saucy Jacky" postcard and also signed "Jack the Ripper", was received past the bureau. It claimed responsibility for the most recent murders on xxx September, and described the murders of the ii women as the "double event", a designation which has endured.[86]

On Tuesday 2 October, an unidentified female person torso was found in the basement of New Scotland One thousand, which was nether construction. It was linked to the Whitechapel murders past the press, but information technology was not included in the Whitechapel murders file, and any connection between the ii is now considered unlikely.[87] The example became known every bit the Whitehall Mystery.[87] On the aforementioned twenty-four hour period, the psychic Robert James Lees visited Scotland Yard and offered to track downwardly the murderer using paranormal powers; the police force turned him away and "called [him] a fool and a lunatic".[88]

The head of the CID, Anderson, somewhen returned from get out on 6 Oct and took charge of the investigation for Scotland Yard. On sixteen October, George Lusk of the Whitechapel Vigilance Commission received some other letter claiming to be from the killer. The handwriting and style were different that of the "Honey Boss" letter and "Saucy Jacky" postcard. The letter arrived with a small box containing one-half of a homo kidney preserved in alcohol. The letter'southward author claimed that he had extracted information technology from the torso of Eddowes and that he had "fried and ate" the missing half.[89] Opinion on whether the kidney and the letter of the alphabet were genuine was and is divided.[90] By the end of October, the police had interviewed more than than 2,000 people, investigated "upwards of 300", and detained fourscore.[91]

Mary Jane Kelly [edit]

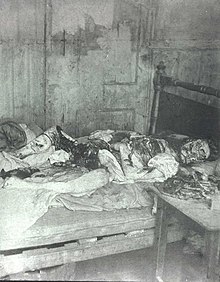

On Fri nine Nov, prostitute Mary Jane Kelly was murdered in the single room where she lived at thirteen Miller's Courtroom, backside 26 Dorset Street, Spitalfields.[92] One of the earlier victims, Chapman, had lived in Dorset Street, and some other, Eddowes, was reported to have occasionally slept crude at that place.[93] Kelly'south severely mutilated torso was discovered shortly later 10:45 am lying on the bed. The first medico at the scene, Dr George Bagster Phillips, believed that Kelly was killed past a slash to the throat.[94] Later her expiry, her abdominal cavity was sliced open up and all her viscera removed and spread around the room. Her breasts had been cut off, her face mutilated across recognition, and her thighs partially cut through to the os, with some of the muscles removed.[95] Unlike the other victims, she was undressed and wore only a light chemise. Her wearing apparel were folded neatly on a chair, with the exception of some found burnt in the grate. Abberline idea the clothes had been burned past the murderer to provide light, as the room was otherwise only dimly lit past a single candle.[96] Kelly'south murder was the well-nigh fell, probably because the murderer had more than time to commit his atrocities in a private room rather than in the street.[97] Her state of undress and folded wearing apparel have led to suggestions that she undressed herself before lying down on the bed, which would betoken that she was killed by someone she knew, by someone she believed to be a client, or when she was asleep or intoxicated.[98]

The coroner for North East Middlesex, Dr Roderick Macdonald, MP,[99] presided over the inquest into Kelly'southward death at Shoreditch Town Hall on 12 Nov.[100] Amid scenes of great emotion, an "enormous crowd" of mourners attended Mary Kelly'southward funeral on 19 November.[101] The streets became gridlocked and the cortège struggled to travel from Shoreditch mortuary to the Roman Cosmic Cemetery at Leytonstone, where she was laid to residuum.[101]

On 8 Nov, Charles Warren resigned as Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police afterwards the Home Secretarial assistant informed him that he could not make public statements without Domicile Office blessing.[102] James Monro, who had resigned a few months before over differences with Warren, was appointed every bit his replacement in Dec.[103] On 10 November, the law surgeon Thomas Bond wrote to Robert Anderson, head of the London CID, detailing the similarities between the 5 murders of Nichols, Chapman, Footstep, Eddowes and Kelly, "no doubt committed by the same paw".[104] On the aforementioned day, the Chiffonier resolved to offer a pardon to any cohort who came forward with information that led to the conviction of the actual murderer.[105] The Metropolitan Law Commissioner reported that the Whitechapel murderer remained unidentified despite 143 extra plain-clothes policemen deployed in Whitechapel in November and Dec.[106]

Rose Mylett [edit]

On Thursday 20 December 1888, a patrolling constable found the strangled trunk of 26-twelvemonth-old prostitute Rose Mylett in Clarke's Yard, off Poplar Loftier Street.[107] Mylett (born Catherine Milett and known as Drunken Lizzie Davis[108] and Fair Alice Downey[109]) had lodged at 18 George Street, as had Emma Smith.[110]

Four doctors who examined Mylett'south body thought she had been murdered, but Robert Anderson thought she had accidentally hanged herself on the neckband of her dress while in a drunken stupor.[111] At Anderson'southward request Dr Bond examined Mylett'southward body, and he agreed with Anderson.[112] Commissioner Monro also suspected it was a suicide or natural death as in that location were no signs of a struggle.[113] The coroner, Wynne Baxter, told the inquest jury that "there is no bear witness to show that expiry was the result of violence".[114] Nevertheless, the jury returned a verdict of "wilful murder against some person or persons unknown" and the case was added to the Whitechapel file.[115]

Alice McKenzie [edit]

Alice McKenzie, 40, lived in a lodging-firm at 52 Gun Street.[116]

Alice McKenzie was possibly a prostitute,[117] and was murdered at nearly 12:forty am on Wednesday 17 July 1889 in Castle Aisle, Whitechapel. Like most of the previous murders, her left carotid avenue was severed from left to right and there were wounds on her abdomen. However, her wounds were not as deep as in previous murders, and a shorter blade was used. Commissioner Monro[118] and one of the pathologists examining the body, Bond, believed this to exist a Ripper murder, though another of the pathologists, Phillips, and Robert Anderson disagreed,[119] as did Inspector Abberline.[120] Later writers are likewise divided, and either suggest that McKenzie was a Ripper victim,[121] or that the unknown murderer tried to brand it expect like a Ripper killing to deflect suspicion from himself.[122] At the inquest, Coroner Baxter acknowledged both possibilities, and concluded: "In that location is not bad similarity between this and the other class of cases, which have happened in this neighbourhood, and if the aforementioned person has non committed this crime, it is conspicuously an imitation of the other cases."[123]

Pinchin Street torso [edit]

Contemporary illustration of the discovery of the Pinchin Street torso

A woman'south torso was found at 5:15 a.m. on Tuesday 10 September 1889 under a railway curvation in Pinchin Street, Whitechapel.[124] Extensive bruising well-nigh the victim'due south back, hip, and arm indicated that she had been severely beaten presently before her death, which had occurred approximately one day prior to the discovery of her body. The victim's belly was also extensively mutilated in a manner reminiscent of the Ripper, although her genitals had non been wounded.[125] The dismembered sections of the body are believed to have been transported to the railway arch, hidden under an old chemise.[126] The historic period of the victim was estimated at xxx–40 years.[127] Despite a search of the surface area, no other sections of her body were always found, and neither the victim nor the culprit were ever identified.[125]

Principal Inspector Swanson and Commissioner Monro noted that the presence of blood within the body indicated that decease was not from haemorrhage or cut of the throat.[128] The pathologists, even so, noted that the general bloodlessness of the tissues and vessels indicated that haemorrhage was the cause of death.[129] Newspaper speculation that the trunk belonged to Lydia Hart, who had disappeared, was refuted after she was found recovering in hospital after "a bit of a spree".[130] Some other claim that the victim was a missing daughter called Emily Barker was also refuted, equally the torso was from an older and taller woman.[130]

Swanson did non consider this a Ripper case, and instead suggested a link to the Thames Torso Murders in Rainham and Chelsea, also equally the "Whitehall Mystery".[131] Monro agreed with Swanson's assessment.[132] These 3 murders and the Pinchin Street case are suggested to exist the work of a serial killer, nicknamed the "Torso killer", who could either be the same person as "Jack the Ripper" or a split killer of uncertain connection.[133] Links between these and three farther murders—the "Battersea Mystery" of 1873 and 1874, in which two women were found dismembered, and the 1884 "Tottenham Court Route Mystery"—take besides been postulated.[134] [135] Experts on the murders—colloquially known as "Ripperologists"—such as Stewart Evans, Keith Skinner, Martin Fido, and Donald Rumbelow, disbelieve whatever connectedness between the torso and Ripper killings on the ground of their unlike modi operandi.[136]

Monro was replaced as Commissioner by Sir Edward Bradford on 21 June 1890, subsequently a disagreement with the Dwelling Secretary Henry Matthews over law pensions.[137]

Frances Coles [edit]

Frances Coles lived in a lodging-house in White's Row.[138]

The last of the murders in the Whitechapel file was committed on Friday 13 February 1891 when prostitute Frances Coles was murdered under a railway arch in Swallow Gardens, Whitechapel. Her body was found only moments subsequently the attack at two:15 am. by PC Ernest Thompson, who after stated he heard retreating footsteps in the distance.[139] Equally gimmicky police practices dictated, Thompson remained at the scene.[140]

Coles was lying below a passageway nether a railway curvation between Chamber Street and Royal Mint Street. She was still alive, but died earlier medical help could arrive.[141] Minor wounds on the back of her head propose that she was thrown violently to the ground before her throat was cut at least twice, from left to right and then dorsum once more.[142] Otherwise there were no mutilations to the body, leading some to believe Thompson had disturbed her assailant.[143] Superintendent Arnold and Inspector Reid arrived soon afterwards from the nearby Leman Street law station, and Main Inspectors Donald Swanson and Henry Moore, who had been involved in the previous murder investigations, arrived by 5 am.[144]

A homo named James Sadler, who had earlier been seen with Coles, was arrested by the police force and charged with her murder. A high-profile investigation past Swanson and Moore into Sadler'due south past history and his whereabouts at the fourth dimension of the previous Whitechapel murders indicates that the police may have suspected him to be the Ripper.[145] Notwithstanding, Sadler was released on iii March for lack of bear witness.[145]

Legacy [edit]

The murderer or murderers were never identified and the cases remain unsolved. Sensational reportage and the mystery surrounding the identity of the killer or killers fed the evolution of the character "Jack the Ripper", who was blamed for all or most of the murders.[47] Hundreds of books and articles discuss the Whitechapel murders, and they feature in novels, short stories, comic books, television shows, and films of multiple genres.[146]

The poor of the East End had long been ignored by affluent gild, but the nature of the Whitechapel murders and of the victims' impoverished lifestyles drew national attention to their living weather.[147] The murders galvanised public stance against the overcrowded, unsanitary slums of the Due east End, and led to demands for reform.[148] [149] On 24 September 1888, George Bernard Shaw commented sarcastically on the media's sudden business organisation with social justice in a letter to The Star newspaper:[150]

Whilst we conventional Social Democrats were wasting our time on education, agitation and organisation, some independent genius has taken the matter in manus, and by simply murdering and disembowelling ... women, converted the proprietary press to an inept sort of communism.

Acts of Parliament, such every bit the Housing of the Working Classes Human action 1890 and the Public Wellness Amendment Act 1890, set minimum standards for accommodation in an try to transform degenerated urban areas.[151] The worst of the slums were demolished in the two decades following the Whitechapel murders.[152]

Abberline retired in 1892, and Matthews lost part in that year's full general election. Arnold retired the following year, and Swanson and Anderson retired afterwards 1900. At that place are no documents in the Whitechapel murder file dated later on 1896.[153]

Encounter also [edit]

- List of fugitives from justice who disappeared

- List of murderers by number of victims

- List of series killers before 1900

References [edit]

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ Greenwood, James (1883), In Foreign Company, London, p. 158, quoted in Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. 21, 45

- ^ Daily Mail, 16 July 1901, quoted in Werner (ed.), pp. 62, 179

- ^ Pall Mall Gazette, 4 Nov 1889, quoted in Evans and Rumbelow, p. 225 and Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 516

- ^ Honeycombe, The Murders of the Black Museum: 1870–1970, p. 54

- ^ Werner (ed.), pp. 42–44, 118–122, 141–170

- ^ Rumbelow, Consummate Jack The Ripper p. 14

- ^ Rumbelow, Jack the Ripper: The Consummate Casebook p. xxx

- ^ White, Jerry (2007), London in the Nineteenth Century, London: Jonathan Cape, ISBN 978-0-224-06272-v, pp. 323–332

- ^ Marriott, p. 207

- ^ Lloyd, pp. 51–52

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 14

- ^ a b c "The Enduring Mystery of Jack the Ripper" Archived iv February 2010 at the Wayback Motorcar, Metropolitan Police, retrieved 1 May 2009

- ^ Cook, pp. 33–34; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 3

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 47; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 4; Fido, p. fifteen; Rumbelow, p. 30

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. 27–29; Melt, pp. 34–35; Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 47–50; Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 4–7

- ^ Whitehead and Rivett, p. 18

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 47–l

- ^ Dew, Walter (1938), I Caught Crippen, London: Blackie and Son, p. 92, quoted in Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 29

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 29

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 28; Evans and Skinner, The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook, pp. 4–7

- ^ Marriott, pp. 5–7

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. 29–31; Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 47–l; Marriott, pp. v–7

- ^ Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 11; Whitehead and Rivett, p. 19

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 51–52

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. 51–53; Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 51–55; Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 8–18; Marriott, pp. 9–14

- ^ In an interview reported in the Pall Mall Gazette, 24 March 1903, Inspector Frederick Abberline referred to "George-yard, Whitechapel-route, where the first murder was committed" (quoted in Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 56). Walter Dew wrote in his memoirs, that "there can be no doubtfulness that the August Bank Holiday murder ... was the handiwork of the Ripper" (I Caught Crippen, p. 97, quoted in Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 56). In his memoirs, Assistant Commissioner Robert Anderson said the second murder occurred on 31 Baronial (quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 632).

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 515; Marriott, p. 13

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. 85–85; Evans and Rumbelow, p. 61; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 24

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 60–61; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 35; Rumbelow, pp. 24–27

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 64

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 98; Cook, pp. 25–28; Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 62–63

- ^ Cook, pp. 25–28; Woods and Baddeley, pp. 21–22

- ^ "Another Terrible Murder in Whitechapel". The Waterford News. nine November 1888. Retrieved 22 Baronial 2021.

- ^ Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 676, 678

- ^ Marriott, pp. 21–22

- ^ Marriott, pp. 22–23

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 66–73; Whitehead and Rivett, pp. 33–34

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 66–70

- ^ Cook, p. 221; Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 71–72; Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 67–68, 87; Marriott, pp. 26–29; Rumbelow, p. 42

- ^ Fido, p. 35; Marriott, pp. 77–79

- ^ Marriott, pp. 77–79

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 157; Melt, pp. 65–66; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 29; Marriott, pp. 59–75; Rumbelow, pp. 49–l

- ^ a b Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 153; Cook, p. 163; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 98; Marriott, pp. 59–75

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 153; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 100; Marriott, pp. 59–75

- ^ Connell, pp. 15–16; Cook, p. ninety

- ^ Connell, pp. 19–21; Rumbelow, pp. 67–68

- ^ a b c Davenport-Hines

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 159–160; Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 111–119, 265–290

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 186

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 65

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 205; Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 84–85

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 86

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. 46, 168–170; Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 96–98; Rumbelow, pp. 69–lxx

- ^ a b Cook, p. 157; Woods and Baddeley, p. 86

- ^ See for example Stewart, William (1939), Jack the Ripper: A New Theory, Quality Press, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 418

- ^ Marriott, pp. 81–125

- ^ e.g. Melville Macnaghten quoted past Cook, p. 151; Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 584–587 and Rumbelow, p. 140; Thomas Bond (British dr.) quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 360–362 and Rumbelow, pp. 145–147

- ^ Inquest testimony of surveyor Frederick William Foster, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 201–202; Marriott, p. 138

- ^ Examining pathologist Dr Frederick Gordon Brownish quoted in Fido, pp. 70–73 and Marriott, pp. 130–131

- ^ Marriott, pp. 132–144; Whitehead and Rivett, p. 68

- ^ Examining pathologist Dr Frederick Gordon Brown quoted in Evans and Rumbelow, p. 128; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 207; and Marriott, pp. 132–133, 141–143

- ^ Sequeira's inquest testimony quoted in Evans and Rumbelow, p. 128; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 208; and Marriott, p. 144

- ^ Saunders's inquest testimony quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 208

- ^ Cook, pp. 45–47; Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 178–181

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. 46, 189; Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 114–116; Marriott, p. 81

- ^ Constable Alfred Long's inquest testimony, quoted in Marriott, pp. 148–149 and Rumbelow, p. 61

- ^ Alphabetic character from Charles Warren to Godfrey Lushington, Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Home Section, 6 November 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 183–184

- ^ Detective Constable Daniel Halse's inquest testimony, eleven Oct 1888, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 214–215 and Marriott, pp. 150–151

- ^ Letter of the alphabet from Charles Warren to the Home Office Undersecretary of State, half dozen November 1888, quoted in Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 197; Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 183–184 and Marriott, p. 159

- ^ Inquest testimony of surveyor Frederick William Foster, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 201–202

- ^ Rumbelow, p. 76

- ^ Testimony of Dr Blackwell, the commencement surgeon at the scene, quoted by Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 163 and Rumbelow, p. 71

- ^ Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 175; Rumbelow, p. 76

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. 186–187; Cook, pp. 166–167; Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 106–108; Rumbelow, p. 76

- ^ Begg, pp. 186–187; Melt, p. 167; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 164; Rumbelow, p. 76

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 104; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 158; Rumbelow, p. 72

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 106–108; Rumbelow, p. 76

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. 176–184

- ^ Reported in The Times, ii October 1888

- ^ Inspector Donald Swanson'due south report to the Home Office, nineteen October 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 193

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. 193–194; Principal Inspector Swanson's report, 6 November 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 24–25; Fido, pp. 45, 77

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. 201–203; Fido, pp. 80–81

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 202; Evans and Rumbelow, p. 141; Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 179, 225; Fido, p. 77

- ^ Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 291–299; Fido, p. 134

- ^ Cook, pp. 76–77; Woods and Baddeley, pp. 48–49

- ^ Evans and Skinner (2001), p. 30; Rumbelow, p. 118

- ^ a b Evans and Rumblelow, pp. 142–144; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 239

- ^ Lees's diary quoted in Forest and Baddeley, p. 66

- ^ Quoted in Evans and Rumbelow, p. 167; Evans and Skinner (2001), p. 63; Primary Inspector Swanson's report, 6 November 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 185–188 and Rumbelow, p. 118

- ^ Cook, pp. 144–149; Evans and Skinner (2001), pp. 54–71; Fido, pp. 78–80; Rumbelow, p. 121

- ^ Inspector Donald Swanson's written report to the Home Function, xix Oct 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 205; Evans and Rumbelow, p. 113; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 125

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 231; Evans and Rumbelow, p. 177

- ^ Daily Telegraph, 10 Nov 1888, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 339

- ^ Dr Phillips'due south inquest testimony, 12 November 1888, quoted in Marriott, p. 176

- ^ Constabulary surgeon Thomas Bail's written report, MEPO iii/3153 ff. 10–eighteen, quoted in Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. 242–243; Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 345–347 and Marriott, pp. 170–171

- ^ Inspector Abberline's inquest testimony, 12 November 1888, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 375–376 and Marriott, p. 177

- ^ Daily Telegraph, 10 November 1888, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 338; Marriott, p. 179; Whitehead and Rivett, p. 86

- ^ Marriott, pp. 167–180

- ^ Marriott, p. 172

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 175, 189; Fido, p. 95; Rumbelow, pp. 94 ff.

- ^ a b East London Advertiser, 21 Nov 1888, quoted in Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 247

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 174; Telegram from Prime Minister Lord Salisbury to Queen Victoria, xi November 1888, Royal Archives VIC/A67/20, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 357; Fido, p. 137; Whitehead and Rivett, p. 90

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 196

- ^ Letter of the alphabet from Thomas Bail to Robert Anderson, 10 November 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 360–362 and Rumbelow, pp. 145–147

- ^ Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 347–349

- ^ Letter of the alphabet to the Home Office of eighteen July 1889 and Commissioner's Study for 1888, quoted in Evans and Rumbelow, p. 204

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 245–246; Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 422–447

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Facts, p. 314

- ^ Ryder, Stephen P. "Rose Mylett (1862-1888) a.k.a. Catherine Millett or Mellett, 'Drunken Lizzie' Davis, 'Fair Alice' Downey". Casebook: Jack the Ripper . Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Daily Chronicle, 26 December 1888, quoted in Beadle, William (2009), Jack the Ripper: Unmasked, London: John Blake, ISBN 978-1-84454-688-6, p. 209

- ^ Robert Anderson to James Monro, 11 January 1889, MEPO 3/143 ff. E–J, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 434–436

- ^ Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 433; Fido, pp. 102–103

- ^ Report by James Monro, 23 December 1888, HO 144/221/A49301H ff. 7–14, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 423–425

- ^ Quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 433

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 245–246

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 205–209; Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 448–468

- ^ Rumbelow, p. 129

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 207–208; Evans and Skinner (2001), p. 137

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 208–209; Marriott, pp. 182–183

- ^ Interview in Cassell's Saturday Journal, 28 May 1892, quoted in Evans and Rumbelow, p. 225

- ^ Marriott, p. 195

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 209

- ^ Coroner Baxter's summing up, 14 August 1888, quoted in Marriott, p. 193

- ^ Eddleston, p. 129

- ^ a b Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Facts, p. 316

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 210; Evans and Skinner, The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook, pp. 480–515

- ^ Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 489–510

- ^ Report to the Abode Part past Swanson, 10 September 1889, MEPO 3/140 ff. 136–40, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 480–482; Written report to the Home Function by Monro, xi September 1889, HO 144/221/A49301K ff. 1–8, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 492–494

- ^ Report of Dr Charles A. Hebbert, sixteen September 1889, MEPO three/140 ff. 146–7, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 496–497; inquest testimony of George Bagster Phillips, 24 September 1889, quoted in Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 509–510

- ^ a b Evans and Rumbelow, p. 213

- ^ Study to the Dwelling house Office past Swanson, x September 1889, MEPO iii/140 ff. 136–40, quoted in Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 210–213 and Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 480–482

- ^ Report to the Home Office by Monro, xi September 1889, HO 144/221/A49301K ff. i–8, quoted in Evans and Rumbelow, p. 213 and Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 492–494

- ^ Gordon, R. Michael (2002), The Thames Body Murders of Victorian London, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-1348-5

- ^ Spicer, Gerard. "The Thames Body Murders of 1887–89". Casebook: Jack the Ripper . Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ Trow, M. J. (2011). The Thames Torso Murders. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Wharncliffe Books. ISBN978-i-84884-430-8.

the Thames trunk murderer has gripped readers and historians ever since he committed his crimes in the 1870s and 1880s

- ^ Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 480; Fido, p. 104; Rumbelow, p. 132

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 217

- ^ Fido, p. 113; Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 551–557

- ^ Ryder, Stephen P. "Frances Coles a.g.a. Frances Coleman, Frances Hawkins, 'Carroty Nell'". Casebook: Jack the Ripper . Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 317

- ^ Melt, pp. 53–55; Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 218–219; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 551

- ^ Examining pathologist Dr Phillips, and Dr F. J. Oxley, offset doctor at the scene, quoted in Marriott, p. 198

- ^ Cook, p. 237; Marriott, p. 198

- ^ Fido, pp. 104–105

- ^ a b Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 220–222; Evans and Skinner (2000), pp. 551–568

- ^ Jenkins, John Philip. "Jack the Ripper". britannica.com . Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. one–2

- ^ Cook, pp. 139–141; Werner (ed.), pp. 236–237

- ^ "The Whitechapel Murders". Western Mail. 17 Nov 1888. Retrieved eleven May 2020.

- ^ Ryder, Stephen P. (editor) (2006), Public Reactions to Jack the Ripper: Letters to the Editor Baronial – December 1888, Chestertown, Maryland: Inklings Printing, ISBN 0-9759129-7-6; Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, pp. i–2; Woods and Baddeley, pp. 144–145

- ^ Werner (ed.), pp. 236–237

- ^ Werner (ed.), pp. 177–179; See as well: "The Fossan (Keate and Tonge) manor", Survey of London: volume 27: Spitalfields and Mile End New Town (1957), pp. 245–251, retrieved 18 January 2010

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 223; Evans and Skinner (2000), p. 655

Bibliography [edit]

- Begg, Paul (2003). Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History. London: Pearson Education. ISBN 0-582-50631-X

- Begg, Paul (2006). Jack the Ripper: The Facts. Anova Books. ISBN 1-86105-687-seven

- Connell, Nicholas (2005). Walter Dew: The Man Who Caught Crippen. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-3803-7

- Melt, Andrew (2009). Jack the Ripper. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84868-327-three

- Davenport-Hines, Richard (2004). "Jack the Ripper (fl. 1888)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Printing. Subscription required for online version.

- Evans, Stewart P.; Rumbelow, Donald (2006). Jack the Ripper: Scotland M Investigates. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-4228-2

- Evans, Stewart P.; Skinner, Keith (2000). The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. London: Constable and Robinson. ISBN i-84119-225-2

- Evans, Stewart P.; Skinner, Keith (2001). Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2549-3

- Fido, Martin (1987). The Crimes, Death and Detection of Jack the Ripper. Vermont: Trafalgar Square. ISBN 978-0-297-79136-2

- Gordon, R. Michael (2000). Alias Jack the Ripper: Across the Usual Whitechapel Suspects. N Carolina: McFarland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-786-40898-6

- Lloyd, Georgina (1986). One Was Not Plenty: True Stories of Multiple Murderers. Toronto: Runted Books. ISBN 978-0-553-17605-6

- Marriott, Trevor (2005). Jack the Ripper: The 21st Century Investigation. London: John Blake. ISBN 1-84454-103-7

- Rumbelow, Donald (2004). The Complete Jack the Ripper: Fully Revised and Updated. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-fourteen-017395-1

- Waddell, Bill (1993). The Black Museum: New Scotland Chiliad. London: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-90332-5

- Werner, Alex (editor) (2008). Jack the Ripper and the East End. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-8247-two

- Whitehead, Marker; Rivett, Miriam (2006). Jack the Ripper. Harpenden, Hertfordshire: Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-one-904048-69-v

- Whittington-Egan, Richard (2013). Jack the Ripper: The Definitive Casebook. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-445-61768-8

- Woods, Paul; Baddeley, Gavin (2009). Saucy Jack: The Elusive Ripper. Hersham, Surrey: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-3410-five

External links [edit]

- Gimmicky news commodity

- 2018 National Geographic article

- 2014 BBC News commodity

- Casebook: Jack the Ripper

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whitechapel_murders

0 Response to "what happendd to constable daniel in dr blake mysteries after season one"

Post a Comment